EFSA – the European Food Safety Authority based in Parma, Italy – has published its Scientific Opinion on the safety of caffeine, in which it estimates acute and daily intakes that raise no safety concerns for the general healthy population.

The opinion also advises on the consumption of caffeine from all dietary sources in combination with physical exercise, and on the possible risks of consuming caffeine together with alcohol, with other substances found in so-called energy drinks, and with p-synephrine, a substance increasingly found in food supplements.

The assessment was finalised following extensive input from Member States, consumer groups, industry and other interested parties. This included a two-month online consultation and a stakeholder meeting in Brussels.

It is the first time that the risks from caffeine from all dietary sources have been assessed at EU level. A number of risk assessments have been carried out previously by national and other authoritative bodies around the world, which were thoroughly analysed by EFSA’s working group.

The European Commission asked EFSA to carry out its assessment after a number of Member States raised concerns about adverse health effects associated with caffeine consumption – particularly cardiovascular disease, problems related to the central nervous system (for example, interrupted sleep and anxiety), and possible risks to foetal health in pregnant women.

EFSA has also published the following lay summary explaining the conclusions and context of its Scientific Opinion.

Following a request from the European Commission, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies (NDA) was asked to deliver a scientific opinion on the safety of caffeine. Possible interactions between caffeine and other common constituents of so-called “energy drinks”, alcohol, synephrine and physical exercise should also be addressed.

Caffeine is an alkaloid found in various plant constituents, such as coffee and cocoa beans, tea leaves, guarana berries and the kola nut, and has a long history of human consumption. It is an ingredient added to a variety of foods, e.g. baked goods, ice creams, soft candy, cola-type beverages.

Caffeine is also an ingredient of so-called “energy drinks” and it is present in combination with synephrine in a number of food supplements marketed for weight loss and sports performance, among others. Some medicines and cosmetics also contain caffeine. “Energy drinks” most often contain combinations of caffeine, taurine and d-glucurono-γ-lactone, among other ingredients.

Synephrine is a biogenic amine of the chemical group of phenylethanolamines/phenylpropanolamines. The protoalkaloid (–)-p-synephrine is naturally found in bitter orange fruit (Citrus aurantium L.) and other citrus fruits. The presence of (+)-p-synephrine or m-synephrine in food supplements containing C. aurantium extracts is indicative of adulteration. Only (–)-p-synephrine, the natural compound from C. aurantium extracts found in food supplements, is considered in this opinion (referred to as p-synephrine hereafter).

This opinion addresses possible adverse health effects of caffeine consumption from all dietary sources, including food supplements, in the general healthy population and in relevant specific subgroups of the general population (e.g. children, adolescents, adults, the elderly, pregnant and lactating women, subjects performing physical exercise).

Whether other substances present in “energy drinks” (d-glucurono-γ-lactone and taurine), alcohol or p-synephrine may modify the possible adverse health effects of caffeine and/or the doses at which such adverse effects may occur is also addressed.

It is outside the scope of the present opinion to address possible adverse health effects of caffeine given as medicine or administered via routes other than the oral route; in subgroups of the population selected on the basis of a disease condition or in sub-populations with extreme and distinct vulnerabilities due to genetic predisposition or other conditions which may require individual advice; or in combination with medicines and/or drugs of abuse, or in combination with alcohol doses which, by themselves, pose a risk to health (e.g. during pregnancy, binge drinking).

It is also outside the scope of this opinion to assess possible beneficial health effects of caffeine or of particular dietary sources of caffeine.

The Panel interprets the request from the European Commission as follows:

- to provide advice on a daily intake of caffeine from all sources which, if consumed ad libitum and throughout the day for long periods of time, does not give rise to concerns about harmful effects to health for the healthy population, divided into various life-stage groups as appropriate;

- for the specific group of individuals performing physical activity, to advise on caffeine consumption (dose and timing) prior to physical activity which does not give rise to concerns about harmful effects to health for this population subgroup; and

- to advise on whether or not, and if so to what extent, the consumption of caffeine together with other food constituents (such as alcohol, substances found in energy drinks or p-synephrine) presents a health risk and if additional or different recommendations for caffeine intakes need to be provided, regarding either the dose of caffeine or the time interval between the consumption of caffeine and the aforementioned food constituents.

The EFSA Comprehensive European Food Consumption Database was used to calculate caffeine intake from food and beverages. It contains data from 39 surveys in 22 different European countries for a total of 66 531 participants. These surveys do not provide information about the consumption of caffeine-containing food supplements. The EFSA report on energy drinks was used to calculate caffeine intakes from “energy drinks” in a “single session” in adults, either alone or in combination with physical exercise.

Owing to the abundance of scientific literature available, previous risk assessments on the safety of caffeine consumption in humans conducted by authoritative bodies will be reviewed first to identify the major health concerns raised in relation to the consumption of caffeine, either alone or in combination with other components of “energy drinks”, alcohol or p-synephrine, and the specific population subgroups which are relevant for the assessment.

The Panel reviewed the literature reporting on the effects of single and repeated doses of caffeine consumed within a day, either alone or in combination with other constituents of “energy drinks” and with p-synephrine, on cardiovascular outcomes, hydration and body temperature in adults, both at rest and in relation to physical exercise. The effects of single and repeated doses of caffeine consumed within a day on the central nervous system were assessed in adults (sleep, anxiety, perceived exertion during exercise and subjective perception of alcohol intoxication) and children (sleep, anxiety and behavioural changes). Adverse effects of longer-term and habitual caffeine consumption were evaluated in children in relation to behavioural changes and in pregnant women in relation to adverse birth weight-related outcomes (e.g. fetal growth retardation, small for gestational age) in the offspring. In adults, the adverse effects of habitual caffeine consumption, either alone or in combination with other constituents of “energy drinks” and with p-synephrine, were evaluated in relation to cardiovascular outcomes. The scientific publications identified almost exclusively reported no relationship or an inverse relationship between habitual caffeine intake and other adverse health effects.

The scientific assessment is based on human intervention and observational studies with adequate control for confounding variables, which have been conducted in healthy subjects at recruitment. Whenever available, human intervention studies and prospective cohort studies have been preferred over case–control and cross-sectional studies because of the lower risk of reverse causality and recall bias. Case reports of adverse events have not been considered for the scientific assessment. Systematic reviews and meta-analysis have been used to summarise the scientific evidence whenever available.

On the basis of the data available, the NDA Panel reached the following conclusions on caffeine intakes which do not give rise to safety concerns for specific groups of the general population.

Adults

Single doses of caffeine

Single doses of caffeine up to 200 mg (about 3 mg/kg bw for a 70-kg adult) from all sources do not give rise to safety concerns for the general healthy adult population. The same amount of caffeine does not give rise to safety concerns when consumed less than two hours prior to intense physical exercise under normal environmental conditions. No studies are available in pregnant women or middle-aged/elderly subjects undertaking intense physical exercise. Single doses of 100 mg (about 1.4 mg/kg bw for a 70-kg adult) of caffeine may increase sleep latency and reduce sleep duration in some adult individuals, particularly when consumed close to bedtime.

Other common constituents of “energy drinks” at concentrations commonly present in such beverages (typically about 300–320, 4 000 and 2 400 mg/L of caffeine, taurine and d-glucurono-γ-lactone, respectively) would not affect the safety of single doses of caffeine up to 200 mg. Up to these levels of intake, other common constituents of “energy drinks” are not expected to adversely interact with caffeine on its effects on the cardiovascular system, the central nervous system or hydration status. Alcohol consumption at doses up to about 0.65 g/kg bw, leading to a blood alcohol concentration of about 0.08 %, would not affect the safety of single doses of caffeine up to 200 mg from any dietary source, including “energy drinks”. Up to these levels of intake, caffeine is unlikely to mask the subjective perception of alcohol intoxication.

The human intervention studies on which these conclusions are based were primarily conducted with caffeine supplements for most of the outcomes assessed (i.e. changes in myocardial blood flow, hydration status, body temperature, perceived exertion/effort during exercise, sleep). Changes in blood pressure were assessed using caffeine supplements, coffee, tea and “energy drinks” as sources of caffeine, whereas the subjective perception of alcohol intoxication was tested using caffeine either from supplements or from “energy drinks”.

The question of whether or not p-synephrine modifies the acute cardiovascular effects of single doses of caffeine has not been adequately investigated in humans, particularly if consumed shortly before intense physical exercise, and therefore no conclusions could be drawn.

About 6 % of the adult population may exceed 200 mg of caffeine in a single session of “energy drink” consumption, and about 4 % do so in connection with physical exercise. This information is not available for other sources of caffeine.

Habitual caffeine consumption

Caffeine intakes from all sources up to 400 mg per day (about 5.7 mg/kg bw per day for a 70-kg adult) consumed throughout the day do not give rise to safety concerns for healthy adults in the general population, except pregnant women (see below).

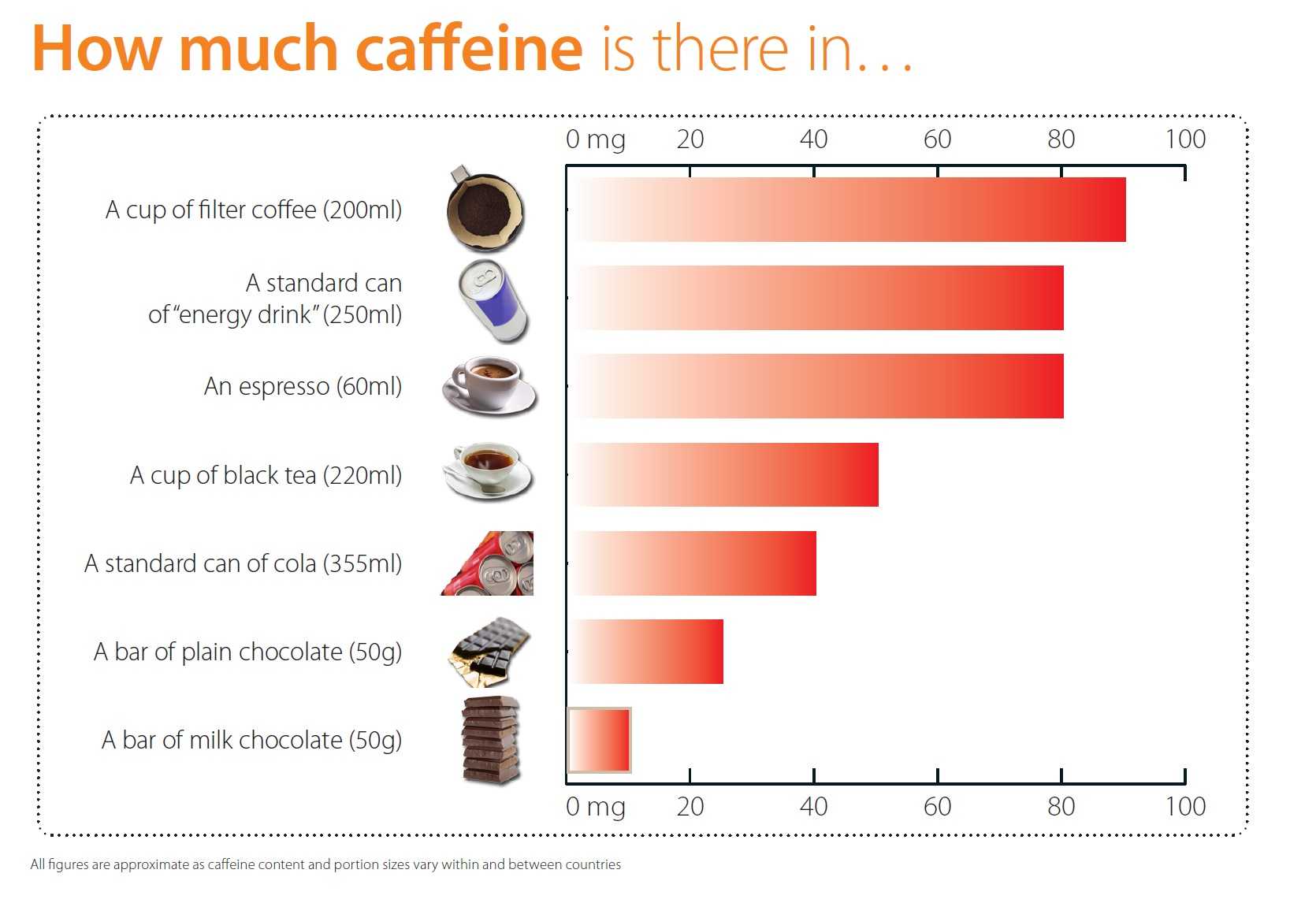

Given the fact that an espresso contains about 60 milligrams of caffeine, it is safe to say that six espresso a day (or two cups of filter coffee) will not do any harm.

No health concerns in relation to acute toxicity, bone status, cardiovascular health, cancer risk or male fertility have been raised by other bodies in previous assessments for this level of habitual caffeine consumption and no new data have become available on these or other clinical outcomes which could justify modifying these conclusions.

Other common constituents of “energy drinks” at the doses commonly present in such beverages and/or moderate habitual alcohol consumption would not affect the safety of habitual caffeine consumption up to 400 mg per day.

The question of whether or not p-synephrine modifies the acute cardiovascular effects of single doses of caffeine or the long-term effects of caffeine on the cardiovascular system has not been adequately investigated in humans and therefore no conclusions could be drawn.

In 7 out of 13 countries, the 95th percentile of daily caffeine intake from foods and beverages exceeded 400 mg. In these countries, the estimated proportion of the adult population exceeding daily intakes of 400 mg ranged from about 6 % to almost one-third (33 %), and coffee was the main source of caffeine. More accurate estimates of caffeine intakes within a given country could be obtained by using national caffeine occurrence data, if available.

Pregnant women

Single doses of caffeine

There are no studies on the health effects of single doses of caffeine consumed by pregnant women prior to intense physical exercise. With regard to the different kinetics of caffeine in this population subgroup, single doses of caffeine which are of no safety concern for non-pregnant adults do not apply to pregnant women performing physical exercise.

Habitual caffeine consumption

Caffeine intakes from all sources up to 200 mg per day consumed throughout the day by pregnant women in the general population do not give rise to safety concerns for the fetus. This conclusion is based on prospective cohort studies showing a dose-dependent positive association between caffeine intakes during pregnancy and the risk of adverse birth weight-related outcomes (i.e. fetal growth retardation, small for gestational age) in the offspring. In these studies, the contribution of “energy drinks” to total caffeine intake was low (about 2 %).

Data to characterise the risk of habitual caffeine consumption in this population subgroup are scarce.

Lactating women

Single doses of caffeine and habitual caffeine consumption

Single doses of caffeine up to 200 mg and habitual caffeine consumption at doses of 200 mg per day consumed by lactating women in the general population do not give rise to safety concerns for the breastfed infant. At these doses of caffeine, daily caffeine intakes by the breastfed infant would not exceed 0.3 mg/kg bw, which is 10-fold below the lowest dose of 3 mg/kg bw tested in a dose finding study and at which no adverse effects were observed in the majority of infants.

There are no data to characterise the risk of single doses of caffeine consumed by lactating women, and data on habitual caffeine consumption in this population subgroup are scarce.

Children and adolescents

The information available for this population subgroup on the relationship between caffeine intakes and health outcomes is insufficient to derive a safe level of caffeine intake.

Single doses of caffeine

Single doses of caffeine of no concern derived for adults (3 mg/kg bw per day) may also apply to children, considering that caffeine clearance in children and adolescents is at least that of adults, and that the limited studies available on the acute effects of caffeine on anxiety and behaviour in children and adolescents support this level of no concern. Like for adults, caffeine doses of about 1.4 mg/kg bw may increase sleep latency and reduce sleep duration in some children and adolescents, particularly when consumed close to bedtime.

There are no data available to characterise the risk of single doses of caffeine from all sources consumed by children and adolescents. Estimates of the proportion of single days in which caffeine intake exceeds 3 mg/kg bw among all survey days using the EFSA Comprehensive Database were used as a conservative approximation.

The estimated 95th percentile of caffeine intake from foods and beverages on a single day exceeded 3 mg/kg bw in 6 out of 16 countries for adolescents (10 to < 18 years), in 9 out of 16 countries for children (3 to < 10 years) and in 3 out of 10 countries for toddlers (12 to < 36 months). The proportion of survey days in which the level was exceeded ranged from about 7 to 12 % in adolescents, from 6 to 15 % in children and from 7 to 37 % in toddlers in the aforementioned countries. Chocolate beverages were important contributors to total caffeine intakes in children and toddlers in most countries, and the use of a conservative caffeine value for this food category may have led to an overestimation of caffeine intakes in these age groups.

Habitual caffeine consumption

As caffeine clearance in children and adolescents is at least that of adults, the same levels of no safety concern derived for adults (i.e. 5.7 mg/kg bw) may also apply to children, unless there are data showing a higher sensitivity to the effects of caffeine in this age group (i.e. difference in pharmacodynamics). As only limited studies are available on the longer-term effects of caffeine on anxiety and behaviour in children and adolescents, there is substantial uncertainty regarding longer-term effects of habitual caffeine consumption in this age group. A level of no safety concern of 3 mg/kg bw per day (i.e. the level of no concern derived for single doses of caffeine for adults) is proposed for habitual caffeine consumption by children and adolescents. This approach is rather conservative in relation to the effects of caffeine on the cardiovascular system, but the limited studies available regarding the longer-term effects of caffeine on anxiety and behaviour in children and adolescents support the proposed caffeine intake level of no safety concern.

The estimated 95th percentile of daily caffeine intake from foods and beverages exceeded 3 mg/kg bw in 5 out of 13 countries for adolescents, in 6 out of 14 countries for children (3 to < 10 years) and in 1 out of 9 countries for toddlers (12 to < 36 months). The proportion of subjects exceeding that level of intake in the above-mentioned countries was about 5 to 10 % for adolescents, 6 to 13 % for children and about 6 % for toddlers. Chocolate beverages were important contributors to total caffeine intakes in children and toddlers in most countries, and the use of a conservative caffeine value for this food category may have led to an overestimation of caffeine intakes in these age groups.