by Lauren F Friedman*

Christopher H. Hendon, a postdoctoral fellow in chemistry at MIT, was sitting in a coffee shop near his graduate school in the UK a few years ago when he overheard a conversation between two frustrated baristas.

“They were having problems with coffee that tasted good one day and not another,” he said. While that’s a frustrating mystery for a coffee shop with exacting standards, “from a chemistry point of view, that’s an interesting problem.”

Specialty coffee shops can control where their beans come from and how they are roasted, ground, and brewed, but there’s one crucial factor that can throw a wrench into the whole operation, Hendon found: the water.

To truly brew a perfect cup, it’s not enough to know what kind of beans you’re working with. You also have to know about the chemistry of the water.

What’s in the water?

Most people know that water can be “hard” (full of minerals like magnesium) or “soft” (most distilled water falls into this category). But there’s also natural variation.

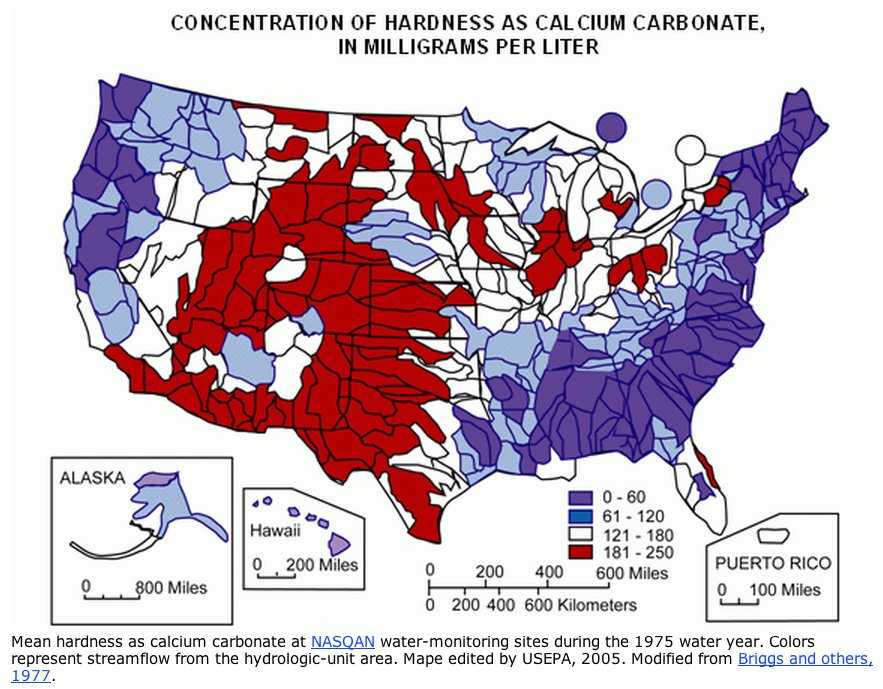

Here’s a map of the US that shows how water hardness varies from place to place. Dark purple shows areas with the softest water, red shows the hardest water, and white and blue are somewhere in between. Hardness can also vary over time:

When Hendon teamed up with baristas Lesley Colonna-Dashwood and Maxwell Colonna-Dashwood — who won the 2015 UK Barista Championship — they found that different kinds of “hardness” in water bring out significantly different flavors in coffee. (Hendon ran the experiments using a computer, while the coffee shop owners actually brewed sample cups.)

So why does the water matter?

Roasted coffee beans are packed with compounds like citric acid, lactic acid, and eugenol (a compound that adds a “woodsy” taste). All of those compounds occur in varying levels in beans, giving coffee its complex and highly varied flavors.

Water, meanwhile, has a complexity all its own. When you turn on a tap, you’re not just getting H2O, but different levels of ions like magnesium and calcium. (Higher levels = “harder.”)

Here’s the key: Some of the compounds in hard water are “sticky,” glomming onto certain compounds in coffee when they meet in your coffee-making device. The more eugenol the water hangs on to, for example, the woodsier the taste of your coffee will be.

Magnesium is particularly sticky, meaning water that’s high in magnesium will make coffee with a stronger flavor (and higher levels of caffeine). Hard water can also have high levels of bicarbonate, though, which Hendon found could lead to more bitter flavors coming through.

But while hard water is a bit of a gamble, depending on which minerals are in the highest concentrations, soft water had no benefits at all. Its chemical composition “results in very bad extraction power,” Hendon explained.

Soft water often contains sodium, but that has no flavor stickiness (for good or bad flavors), Hendon found. That means that if you use the exact same beans, you’ll get a much stronger flavor if you use high-magnesium “hard water” in place of distilled or softened water.

The study was published in the Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, and eventuallyturned into a book that explains why coffee lovers need to worry about more than just good beans. “Water can transform the character of a coffee,” the chemist-barista team explains.

A chemically perfect cup

Unlike Hendon, the average coffee lover is not also a chemist. You can’t easily alter the composition of your water supply every time you want a delicious cup.

But there’s good news: You don’t have to. Understanding that the kind of water you use can change the kind of coffee you get will help you on the path to the perfect brew — even if you’re stuck with whatever comes out of your kitchen tap.

To start, you can look up the hardness of your water online (New Yorkers can call 311), and then buy beans —depending on what you learn — that are meant for “soft” or “hard” water. (Hendon said that’s the kind of thing upscale roasters will know.)

Sure, you won’t know the specific water compounds that will pair perfectly with a particular roast — that’s the kind of rigorous coffee science Hendon and Colonna-Dashwood relied on to place fifth overall in the World Barista Championship — but you’ll already be a step ahead if you buy from a local roaster.

When roasters test their beans, they do so using local water, so you can at least assume that locally-roasted coffee is optimized for the chemistry of your water. That’s the opposite of Starbucks, which, according to Hendon, uses totally pure water to ensure a completely uniform taste across the country.

“A lot of dark art has gone into coffee,” said Hendon. “This is some real science.”