Parked on a bench on Bleecker Street in Manhattan on a dingy Saturday afternoon, I tallied 11 coffees in various forms being clutched, sipped, and toted across my line of vision. There were four coffee shops discernable from my seat.

I Googled, “how many cups of coffee are consumed daily in the US?”

According to the last Experian Simmons National Consumer Study, the answer is 280.5 million. That’s 102 billion cups per year. Oh God, here comes the black hole of caffeine-fueled stats. I dived in deep.

The forecast for worldwide coffee production in 2016-2017 is 158.1 million bags.

The East African country of Tanzania is responsible for around 40,000 metric tons of coffee packed into those bags.

These are big numbers. But they aren’t as shocking as the small number of growers that are in charge of those Tanzanian beans. A collective of 450,000 small-scale farmers produce 90 percent of the coffee in Tanzania. And even more surprising is the economic straits those farmers are facing.

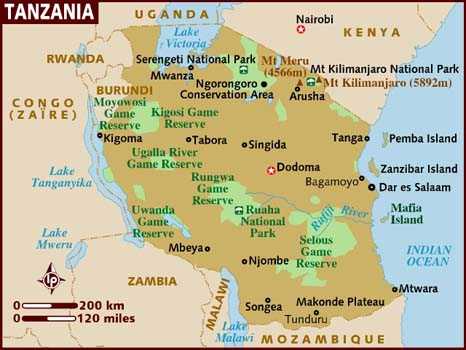

Mama Gladness Pallangyo is the matriarch and sole proprietor of one of Tanzania’s family-owned coffee farms in Tengeru, a village nestled in the highlands of Mt. Meru, located about six miles west of the capital of Arusha.

The land has belonged to her family for more than 70 years. A few cows and chickens wander around the small grassy plot of land Mama Gladness lives on, but about a quarter-mile down a muddy path is the main attraction: a grove of arabica and robusta coffee bean trees resting underneath the banana trees.

For decades, Mama Gladness has hand-harvested and sold her coffee crop in the global market, shipping raw beans to Germany for roasting and marketing.

And like many other Tanzanian growers, she was receiving bargain-basement prices and unable to stay above even a third-world country’s poverty line, due to precarious see-sawing global market prices in conjunction with Tanzania’s changing political structure.

In 1962, the International Coffee Agreement (ICA) took effect and covered most of the exporting and importing countries around the globe. Its goal was to stabilise the price of coffee beans on a wide scale.

But Tanzania was quickly thrown out of the deal when, in 1967, the Tanzanian government implemented one of the most restrictive socialist policies in Africa, cutting coffee growers off from selling directly to private investors. Farmers were suddenly under rigid control, shackled by contracts that allowed them to sell only to government cooperatives directing all the marketing for Tanzanian crops.

By the mid 1970s, the Tanzanian economy had fallen into a deep crisis—only to be taken down deeper when the government pulled a 180 and seemingly overnight became one of the most liberalised countries in Africa in the 1980s.

Sweeping changes within Tanzania’s socialist structure ushered in a free market society; farmers were once again allowed to sell freely into the global market and private investors were able to turn their skeptical interest back to the Tanzanian market, independent from any state control.

But why would they?

Kenya supposedly produced equally high-quality beans but within a more stable political environment. After nearly two decades of subsidised prices, inputs (such as fertilisers and fungicides) became more expensive, while coffee sales became much more unstable—plummeting some seasons well below formerly fixed government prices.

Unpredictable political and economical climates have led coffee growers to pursue other ways of making income, both within and outside of farming activities.

And with tourism counting as the second largest industry in Tanzania (succeeded only by agriculture), combining the two was a natural transition.

Mama Gladness established the Tengeru Cultural Tourism Program (TCTP) alongside her son, Lema Pallangyo, in 2004. TCTP is a product of community-based tourism at its purest form.

The concept that Tanzanian growers could host visitors was inspired by a Danish tourism program with which Mama Gladness was already involved.

That program brought volunteers from foreign countries to African host families—where they could learn more about the culture and their way of living before they went out to work on the field.

One of the volunteers suggested Mama Gladness host tourists to not only teach them about customs, but also coffee.

Fellow villagers weren’t so supportive at first. “Everyone told me that no one would come and that it wouldn’t work,” she says. “They told me, ‘Mama, no one wants stay where cows are.’ But I knew I could do something.”

So she got a toilet, running water, and a brochure and went for it.

Mama Gladness now pairs with travel companies that rely on community-based activities and locally sourced guiding services—such as Intrepid Travel—to connect the dots between travellers seeking bona fide experiences and her countrymen seeking economic respite.

She believed that there would be an interest in experiencing how coffee is grown and learning about its history, just as with wine tourism. Like wine, coffee is largely consumed by first-world countries, but few Western consumers are fluent in the complexities of its production.

I started to acknowledge those complexities as I wandered through the rows of Arabica in the Pallangyo’s grove. Lema told me that this had been a “good year” and plucked one of the red, pebble-like berries off the tree and handed it to me. This berry had taken nine months to arrive to this ripened, ready state.

The harvest season of Tanzania is October to February, and berries don’t ripen uniformly. That requires pickers to select and hand-pick berries as they ripen. After being picked, the berries are dried in the sun until they are at exactly 11 percent moisture content.

We took the dried berries and dropped them into a hulking mortar and pestle to be hulled. While singing traditional Swahili songs, we battered the parchment layer off the cherry to reveal the shiny, slick beans. Within 20 minutes, we were roasting the beans in a tin saucepan over an open flame stove under a thatched roof while it drizzled outside.

“Stir it like a sauce!” Lema directed me whenever my whisking motion slowed down even a beat. We decided on a medium roast—which basically just means that we kept the beans on the flame for nine minutes instead of seven.

When we ground them up in the hand grinder, what came out was a lot less like Chock-Full-O-Nuts grounds and a lot more like a fine espresso powder. But instead of straining the grounds into hot water, we just stirred it right in—like a locavore’s version of Nespresso.

If you had handed me a cup of Nespresso, I probably wouldn’t have been able to taste the difference. But the difference came in being a part of the process and understanding the craft.

Thousands of others visiting Tanzania have shared this same experience and will continue to discover it.

What started as Mama Gladness’s simple idea to open her grove of bananas and arabica beans to tourists quickly turned into a sustainable small-scale industry. TCTP is waived of all taxes by the government, allowing 100 percent of the money it makes to go back to the people involved and to the community of Tengeru.

The income is collected in a fund and is distributed at the end of the year after meeting with representatives from the government to decide what project they would like to take on the following year with the profits.

Since TCTP’s founding, the profits have funded the building of schools, provided school supplies and clean water, built bridges, planted 41 new groves of trees, and created new farms.

“Last year, we were able to paint a map of the world on the wall of the gym in the school with some money that we made,” says Mama Gladness with a smile. “So now [the students] can see where they are and learn about the rest of the world.”

Mama Gladness and her coffee beans have affected more change than she ever anticipated when she printed out her first tourism brochure in 2004.

Kilimanjaro Native Cooperative Union (KNCU), launched a similar program to the TCTP—which constructs Tanzanian coffee tourism on a larger scale.

While TCTP is a singularly-focused program (run by Mama Gladness and benefiting only her village of Tengeru), KNCU is a collective of villages and farmers that work in the coffee industry that work together to promote access to coffee plantations and international sales of beans.

KNCU buys and distributes coffee beans produced by coffee farmers as a full-time business liaison, complete with a department for coffee tourism with two full time people working to get you your batches of Starbucks Reserve Tanzania Mondul and Trader Joes Tanzania Small Lot coffee.

“So many people know very little about the making of coffee and its way from bean to cup,” explains Lema Pallangyo.

“And to share that with them also shares the spirit of what the Cultural Tourism Program is. It creates hope for the whole community, since agriculture and keeping animals was so hard as time went on.

It brings people together, it teaches them, it allows us to share our culture, and gives us enough money to change the economic situation in our village.”

Lauren Steele