A Chinese person drinks five cups of coffee a year on average. In a small town of south China’s Hainan province, however, this rises to 200 a year.

The figure, which is comparable to the world’s average of 240 cups, has impressed international coffee dealers who are seeking to take a share of the market in China.

“I do not believe China will become the world’s largest coffee market in the next decade until I see it for real, but with more middle-income families, the Chinese are drinking more coffee,” said David Kiwanuka, a coffee dealer with the Guangzhou office of Beijing Chenao Coffee Company, a joint venture between China and Uganda.

Fushan in Chengmai county in Hainan, where local farmers started growing coffee in the early 1930s, has nurtured a strong coffee culture. Nearly 100 companies from different countries have opened outlets to promote their brands in the subtropical town.

“I was impressed at how the Chinese love drinking coffee. They have started to show great interest in coffee culture, which has made me see the huge market potential in this country,” said Melaku Legesse, consul general at the Ethiopian Consulate General in Guangzhou.

According to data from the Beijing Coffee Industry Association, coffee consumption growth in the country is increasing at an annual rate of 15%, which is about seven times the average world growth rate.

According to the association, the figure may continue to expand at a pace of 15%-20% annually, making China the most attractive coffee market by 2020.

Despite the fast expansion, it is unlikely that coffee will replace tea as the number one drink of choice in China, given the longstanding tea-drinking tradition in the country, said association chairperson Ji Ming.

Foreign coffee brands were first introduced to China during the 1980s. Brands such as Nestle and Starbucks have played a significant role in creating a coffee culture in the country, according to Ji.

He said the culture is popular in first-tier cities like Beijing and Shanghai, as well as some southern provinces including Hainan and Fujian, although for most other regions, coffee is still viewed as an expensive Western import.

“Even in Beijing and Shanghai, the coffee consumption level remains stubbornly lower than 30 cups per capita,” Ji said, adding that the country’s coffee culture is not sufficiently mature. Annie Huang, general director with the Food and Dining Culture Committee of Guangdong Food Culture Research Institute, said that China’s younger generation with growing purchasing power are willing to pay more for new experiences.

“To them, Starbucks represents a luxurious and fashionable experience. Many of them are attracted by this brand rather than the coffee itself. They can tell what kind of tea is good, but they can’t do so with coffee,” Huang said.

Huang also said, however, that there is huge potential for consumption and that the coffee-drinking culture has not yet reached its peak.

China’s coffee market has been dominated by foreign brands, like Starbucks, Barista Coffee and Blenz, who have taken the lion’s share of the fresh ground coffee market, while Nestle and Maxwell

House are dominating in the instant coffee market.

Since opening its doors in the country in 1999, Starbucks now has 1,001 stores. With China being its second major market, the company plans to expand its outlets to 1,500 by 2015.

The growing number of domestic brands will also help cultivate and invigorate the market.

“Residents in Fushan, old or young, like to spend time in coffee shops. They may not know Starbucks, but they can name every local brand,” said Xu Shibing, chairman of Hainan Coffee Association.

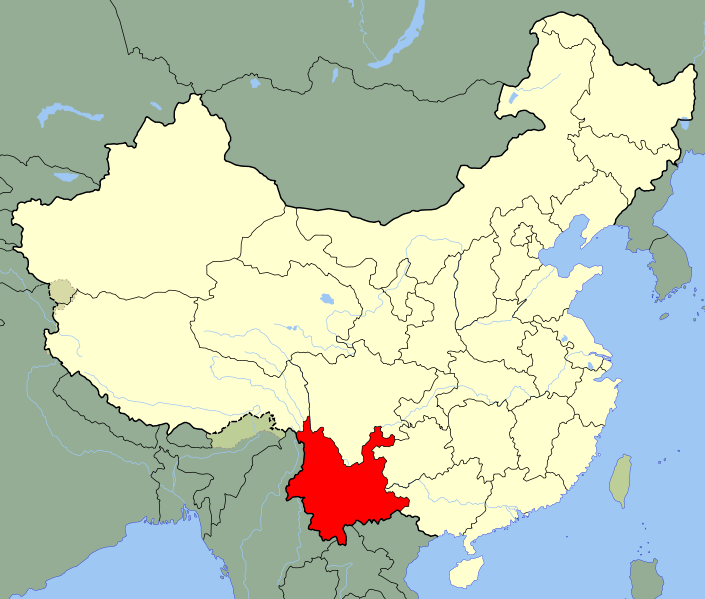

Coffee mainly grows in the provinces of Yunnan, Hainan and Sichuan in China.

Coffee grown in Yunnan accounts for more than 90% of China’s total production, but over half of the output has been exported as crude material over recent years.

Xu said that the country boasts a few domestic coffee brands, mainly small enterprises or crude material producers. Very few of them can compete with foreign brands.

Sophisticated coffee-planting and coffee-making techniques, the lack of professional experience, and the absence of proper industry standards are major challenges for Chinese coffee companies.

Ji said that it is important for the country’s homegrown coffee brands to focus on adapting foreign coffee culture to local consumption habits.