MILAN – Cecafé – the Brazilian Council of Coffee Exporters was created in July 1999 and since then has represented the sector with its 122 members and 96% of the total green exports from Brazil to 147 countries over the last 5 years. We had the opportunity to talk to Cecafè Executive Director Marcos Matos in Milan about the international scene and the critical context brought about by several factors, including climate change, the pandemic, the logistical crisis and rising prices.

Brazil is the world’s largest producer and exporter of green coffee, but also the second largest consumer market for the beverage

What kind of challenges is the Brazilian industry facing in order to be able to supply both the domestic and international markets, considering last year’s low crop cycle and the only partial recovery expected this year due to unfavorable weather conditions?

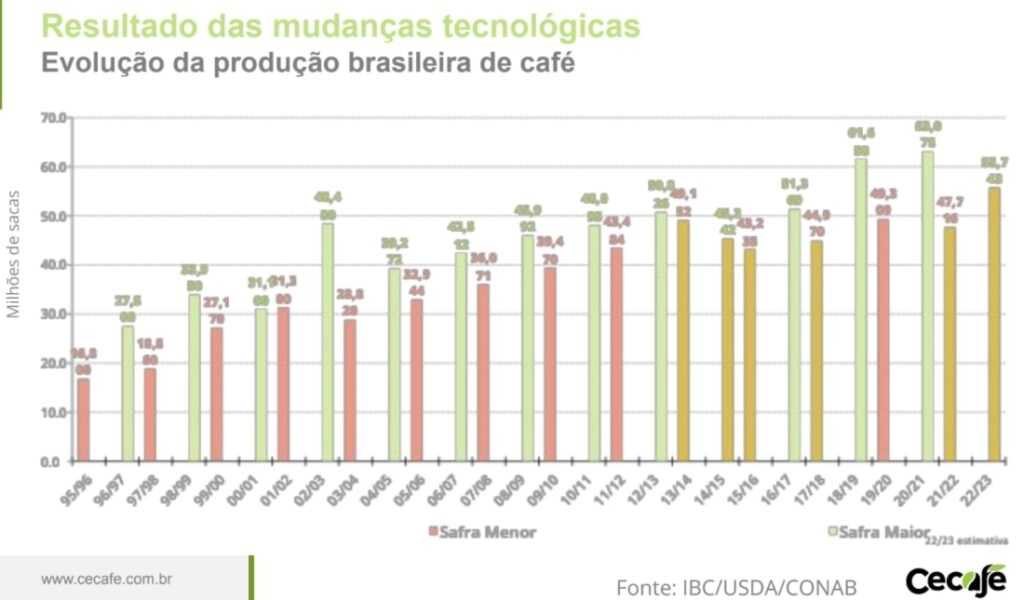

Marco Matos: “Brazil historically invests in research, development and innovation. However, it is important to put this into context in order to understand what we are experiencing today: for example, in the 1960s Brazil produced 6 bags per hectare on an area of 5 million. Today, however, we are talking about 33 bags in 2.1 million hectares. That represents 0.2% of Brazilian territory.

In the last 20 years, Brazil has increased its market presence, reaching 40% of global sales, considering internal consumption and exports. Currently Brazil, being a continental country, suffers from the effect of weather anomalies. 95% of production is concentrated in the Brazilian south-east, the area most subject to climate change.

The 2020 harvest had higher volumes and quality: we produced 63 million bags with 70 million exported according to market estimates, a record figure. But in 2020, we also experienced climate problems that continued into 2021. Coffee is a biennial product: two years of highs correspond to two years of lows. We were already prepared for a lower crop in 2021, but it turned out to be even lower than expected. It went from a production of 63 million bags to 45 million bags.

Climate interference will also affect the 2022 harvest.

In the graph, which shows the trend in productivity over the year, blue indicates the highest yields, red the lowest, indicating the presence of problems until 2013, as many as three harvests that were therefore influenced by the climate. In 2017, there was a dry spell in the Espirito Santo region, affecting Connillon.

The figure of 55.7 again suggests a low harvest, because there was very high consumption and high exports even in the pandemic period. We have to face the climate challenge and also the logistical challenge. Last year, for example, Brazil did not export 3 million bags of coffee because of a lack of space in containers. And indeed, more and more Brazilian exporters are shipping their coffee in large bags and opting for the “break bulk” system to avoid the logistical bottlenecks that continue to plague the entire coffee sector.”

However, experts say that this is only an efficient solution in the short term. How long will it take to get things back to normal? How long will the global logistics crisis last?

“We think the logistics problem will drag on through 2022. And so we want break bulk to be modernized. So we want to proceed with export in the holds of the ship, but with a more technological method: today we use dedicated ships, which break bulk in the holds. But now the coffees are quality blends, so all procedures rely on the use of technology in both loading and unloading. We have made five large shipments since November, each averaging 100,000 bags, and we are expecting as many companies have started to study this method.

So break bulk has actually helped with exports. We know we have logistical problems, just as we know the use of break bulk, and in 2022 we will be able to meet export demand but within a very tight framework: supply and demand with very low storage.”

So what can we expect in terms of storage levels and export quantities for 2022?

“Cecafé’s information base is the certification of origin, which exists in the international agreements of the producing countries. The Brazilian government has entrusted this mission to Cecafé, which represents exporters and supplies the domestic and foreign markets. Under our acronym there are cooperatives, national and international companies, 96% of exports. This means that Cecafé reports what the market has achieved.

We know that 2022 will be a very cold year, just as 2021 was, but we still managed to export 40.6 million bags – the third highest result we have been able to achieve historically. Of course, we cannot compare 2022 with 2020, when we exported 44.7 million bags.

We will certainly see a more limited year but with very good exports and low storage, and we hope for a better 2023 harvest. 2023 can be a very important year for exports because in the summer of 2022 we saw enough rainfall in the country. We still have a few months to analyze the situation better: after the 2022 harvest, there will be the 2023 flowering. Because coffee is a perennial plant, and you need more than one year to analyze its performance.”

Cecafé recently announced a synergy for risk mitigation in exports. Can you tell us more about this initiative?

“We have several initiatives to mitigate risks. Let me tell you a few: one of the focal points is the transmission of better agronomic practices, through the activation of programmes that promote their application together with more effective tools such as rural insurance. All these operations together can cushion the impact: the use of soil cover materials, screens, culture consortia with trees, new technologies, all help to reduce risks. From the point of view of the flow of trade, Cecafè and Serasa Experian (global company) have registered a platform for risk management that can be a reference point for all future

contracts, for producers and exporters, both of which are present on this consolidated system.

And so we make management an educational form of risk assessment and lead producers to use these tools as effectively as possible. Brazil is recognised as a country that respects contracts, both by exporters and producers, even in times when prices rise abnormally. The problem with Brazilian crops and high consumption is that they can together lead to a natural increase in prices. We have had positive feedback about this platform and it has proved to be a very helpful tool.

Cecafé has therefore dialogue with the government, the financial system, the coffee authorities

And has succeeded in making everyone understand that the production chain can develop a modern risk management that rewards the producer who truly fulfills his tasks. We have more than 80% of our export volumes on this established platform. Due to the general law of data protection, producers are not exposed, it is a closed system.

Each member and their negotiated contracts, as well as all member markets are protected. You join as soon as you join Cecafè, and those who want to join have already been found compliant to enter the platform. We of course check the individual conditions of producers who negotiate with exporters or with all members.

In addition to this, Cecafé has been in dialogue with the Ministry of Infrastructure in Brazil, creating and coordinating a working group involving other agri-trade chains, all those who use containers to export: the ministry convenes exporters and shipowners every week.

We consolidated a team to find solutions, even if not in the short term, to draw up a contingency plan. The shipowners have shown great openness and willingness with us, so much so that the figures for January and February show an excellent result in terms of reducing logistical problems: the impact of the container shortage is now more limited. It is still there, but at a much lower level than last year. The problem remains global, between pandemic and post-pandemic, but with the restart of the economies, the world’s main

routes are congested and Brazil remains somewhat off the main routes. So we are more affected.”

Cecafé is famous for collecting data and statistics: what are the criteria by which they are collected and compiled?

“The certificate of origin is our information base, as mentioned before. All exports are collected on it. There is a Cecafé management that is responsible for this segment of data collection and statistics. All export information and each certificate has parameters: country sales, quality, certificates of these sales in terms of quality and sustainability. This is strategic information: all the logistics, the form of cargo packaging, suggest market intelligence. Cecafé also has all the data on the port of origin and price list.

So-called differentiated coffees, for example, are of higher quality or linked to quality and sustainability brands. We exported almost 8 million bags of them last year, which is 40% more than other coffees. Of these, 60% for quality, 40% for sustainability. For example, certificates such as Fairtrade, Rain Forest, and not forgetting illy, account for 20%. But when we look at more important markets like the European Union, 50% of all our sales are 30% of these differentiated coffees. This information helps us right now to understand this market and how it handles commodity imports: any commodity cannot be associated with

deforestation, as it needs traceability. Along with the platform we created with Serasa, we are working on developing another one for tracking available to all our members. A standardized form to meet all needs in an organized manner.”

But Cecafé’s data are not the only ones…

“Cecafé is responsible for export data. For domestic consumption, there is instead an association called ABIC, (Brazilian International Coffee Association) and ABICS for soluble coffee. The estimates they make are based on market analysis and not on institutional sources such as certificates of origin. They have an estimate of domestic consumption, while Cecafé has accurate export documents, so much so that they are able to publish a report every month, which is the main source that specialized journalists look for.

On the production side, they rely on public bodies such as Conabi (national supply company), which records the quantity of bags: it is an estimate, because they are projections, and it makes it difficult for us to analyze consolidated statistics. If we make a study of 10 harvests, with production in one column, domestic consumption in another, exports, we would still be missing part of Brazil’s total production. There are always gaps in the data to give a complete and homogeneous picture. Global statistics also suffer from the

same problem. Even USDA, the US Department of Agriculture, which does this same kind of harvesting, has difficulties.

In 2020 we produced 60 million bags with Conabi, but according to USDA 70 million bags were reported. This is a problem we are working on, to solve it through geolocalisation. A private individual has set up a working group that, together with Conabi, wants to find better ways of collecting data. In addition, Brazil’s Guardia di Finanza says that the certificate of origin must be accompanied by the export document.”

What policies has the Brazilian government put in place to improve conditions for farmers on plantations?

“It is a public and private effort. On the public side there are forms of taxation from the Ministry of Labour. There are specific laws on work between the field and the city and we have a “black list” of rural producers and entrepreneurs linked to degrading working conditions of their officials. But we have in Brazil, according to the last data collection, 265 thousand producers and of these, only eleven names to put on the list. When the government publishes it, we share it with our associates. In the private sector, on the other hand, we have high codes of ethics and conduct signed by our 122 members.

They immediately do not trade in the products of blacklisted members. And they share these references with their own business partners so that they, too, exclude them from their businesses. Each member also has codes of ethics signed with major global roasters. Still on the work front, we have started a programme with international roasters that have written agreements with exporters, coordinated by Cecafè, the global coffee platform and an NGO called Impacto, which is responsible for better working conditions for all production chains in Brazil. So on the basis of this work we recognise two major activities:

working in the concept of better profitability and prevention.

We look at best practices first and use the educational side and not the punitive side, as we are not the government. We also identify the regions with the highest risk based on vulnerability indices using official data. We already know where we have to intervene and the problem may occur and we already implement educational action, transferring the best possible practices. We would like to eliminate exploitation in the production chain. The goal is to reach 5,000 producers.”

There is more and more talk about young people abandoning farming: how is the situation in Brazil?

“According to official data, of the human development index, where coffee is present, this element that measures life expectancy, income, education, development is higher. For example, Minas Gerais, which corresponds to half of the national production, has an average index according to Om. Again in the state of Minas Gerais, where the index is average, in the internal regions where there is coffee production, the level is higher.

There are several mechanisms that have been created to generate this development. Here are some of them: coffee has its own fund in Brazil called Funcafè, which is six billion reales. In addition to this, there is the rural credit system, which is available to everyone: the producer can therefore finance himself with subsidized credit costs. The credit is valid to support production costs, investments, storage and also when a climatic problem

affects production.

For example, in 2021 producers were affected by dry weather and also by frost: Funcafé

allocated 1.3 billion reales to the affected farmers, also giving them many years to repay. The producers received half of this amount. In addition, we know that many farmers have also had access to several credit funds in addition to the coffee funds.

This is one of the points we think is important with the platform of future contracts: because of our super-harvest in 2020, starting in 2019, when the market was already expecting a big harvest, prices came down, 100 a pound/weight. But exchanges have a moment of high even in a period of low value. From late 2019 to 2020, there were 4/5 moments when the stock market reacted. In each moment, producers sold millions of bags, because producers in Brazil are close to cooperatives and exporters. Brazil is the only producing country that uses long-term contracts because of the culture of maintaining and

respecting agreements. At the moment we have been able to achieve good profitability.

We also have another example: for 15 years we have been monitoring and reporting the transfer price for the export of Fob, to the producer. This is an index called IPEP: for 15 years it has fluctuated between 80% and 92%/93%. It means that the transfer is fast and efficient in Brazil: any price change, or more productive negotiation of differentiated coffees with aggregate value, is received by the producer immediately. We started studying this index because of the difficulty of obtaining these numbers in other countries.

Including those in Central America, this index ranges from 40 to 60%: there are more agents in the chain and the process is not so direct. In Brazil, the transfer is faster and the producer is the biggest beneficiary. They have holidays, 13th month, maternity leave and minimum wage. The policy of increasing minimum wages takes into account inflation and GDP growth. Every year the mathematical rule is updated.”

It is also important to mention the legislation focused on the issue of environmental protection, which is very strict compared to other countries. What is Cecafé doing? Where do you stand?

“We consider the environment. Social and economic development has made great progress in the last 20 years. On the environmental side, Brazil approved the forestry code in 2012. The preserved reserves vary from 20 to 80% according to the biome. The consolidated regions in the south 20%/25% and the Amazon, 80%. And the hinterland, the Savannah, 35%. Coffee is almost all consolidated in the south and has requirements of 20%.

In our presentation together with the forestry code, the rural environmental cadastre was formed, which shows the geolocation of properties and where the protected areas and rivers are. They have validated this cadastre with more modern tools. The latest data from the Brazilian research organization Endrapa, which conducted the land register analysis, shows that Brazilian producers are above the required levels. In São Paulo, Minais, Espirito Santo and Bahia, they have 40% more preservation. They are very virtuous.

In Minas Gerais, which has recently been updated, in the coffee production areas alone, Matas de Minas, Sud de Minas and Serrado Mineiro, analyzing the properties and protected areas, we have a total of 1.25 times the surface area of Switzerland. Another topic will be carbon balancy: we are concluding the last phase of this project, analyzing 45 farms in each region by analyzing the production of gases from coffee cultivation. This month we will reveal them.”