The local government has also been promoting the dam’s benefits as a source of irrigation for all types of farming in Pu’er and encouraging the people displaced by Nuozhadu’s reservoir to enter the coffee growing industry. This could be tremendous boon to a region that is now entering its fourth year of serious drought.

High and Dry

Beginning in 2009, Yunnan has seen rainfall decrease by 50 to 60 percent, and over four million peoplehave had difficulty getting drinking water. In addition to coffee, Yunnan is a leading producer of fresh flowers, tobacco, tea, and sugar; the drought halved yields for all of these crops and also caused a 47 percent decrease in reserve hydropower capacity, undermining the investments made in Yunnan’s 21 dams, including Nuozhadu.

Nuozhadu’s reservoir may help ease the impact of the drought, but if it encourages even more agricultural production, it could also exacerbate deforestation, which has significantly reduced the region’s biodiversity and water retention and made it more prone to landslides. The largest culprit behind Yunnan’s deforestation has been the rise of eucalyptus and rubber tree cultivation in the province. Since 1976, over67 percent of Yunnan’s rainforests have been lost due to clear-cutting for rubber plantations. Today, despite an ongoing logging ban, hillsides have been observed being cleared to make way for coffee growing too.

According to Nature, climate change has been a contributing factor in changing weather patterns, including the drought. Xu Jianchu, an ecologist at the Kunming Institute of Botany, said that the most affected areas of Yunnan are those with the fastest rate of development and the most extensivedeforestation. Any change to coffee production therefore has a chance to make a large impact, both in responding to climate change and controlling water use.

A Potential Model for Broader Agricultural Reform?

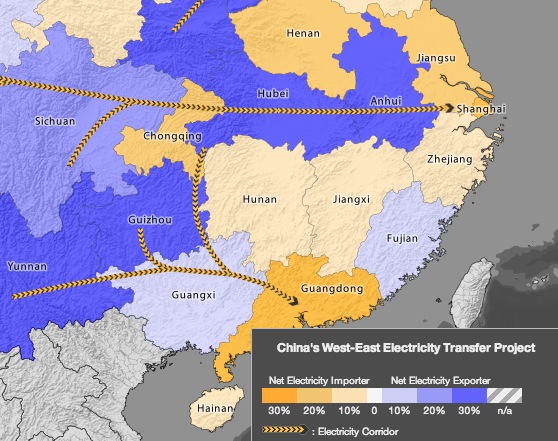

Yunnan is emblematic of the massive competing demands and environmental stresses being felt across China.

Starbucks’ C.A.F.E. Practices, if they can be implemented successfully, offer farmers incentives to reduce water use, stop overuse of fertilizers and pesticides, and implement other sustainable agriculture practices. Previous assessments of C.A.F.E. Practices in Guatemala and Colombia, found that participating farmers were more likely to make investments in water quality and biodiversity.

In turn, less water for coffee could mean more water for everyone else, easing drought pains, improving resilience to climate change, and ensuring hydropower continues to flow to China’s centers of manufacturing. Reducing fertilizer and pesticide use is particularly important as agriculture is China’s largest source of water pollution. Clean water is so scarce in some regions that farmers have been forced to use polluted industrial runoff to water their crops, leading to tainted food.

These market-based incentives could provide a model for sustainable agriculture reforms in China at large. China’s leaders have been masterful in using market incentives to reform agriculture in the past – let’s hope they can do so again.

David Tyler Gibson is a research assistant for the Wilson Center’s China Environment Forum.

Sources: China Daily, China.org, A.K. Chapagain and A.Y. Hoekstra, Circle of Blue, Conservation International, The Economist, International Rivers, International Trade Center, Nature, Reuters, SCS Global Services, Starbucks.

Photo Credit: “Kuanzhai Starbucks, Chengdu,” courtesy of flickr user Navona. Map Credit: James Conkling, fellow at Amnesty International, and David Tyler Gibson.

Source: [via]