MILAN – There is an ongoing clash between Neapolitan coffee culture and that of the rest of Italy, both of which are seeking international recognition for their contributions to world coffee heritage. Specifically, its inclusion in Unesco’s list of “Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.” This unusual rivalry is featured in an article by Pietro Lombardi and Cecilia Butini in a recent issue of the Wall Street Journal. Here are a few excerpts from the article.

According to the story, the spat boils down to a simple question: Who should get the honors for the espresso tradition, Italians or only Neapolitans?

For Neapolitans, at stake is a pillar of their identity. “Neapolitan culture can’t be understood without coffee,” said Marino Niola, an anthropologist at Suor Orsola Benincasa University of Naples. “If you imagine Naples as a body, coffee is the blood flowing through it,” he said.

Back to Unesco’s recognition, two candidates were vying to be the Italian entry. A consortium based in the northeastern city of Treviso (Consortium for the Protection of Traditional Italian Espresso Coffee) put forward an application for recognition of traditional Italian espresso. An opposing bid came from Naples, which sought recognition for the Neapolitan coffee culture.

In March, the Italian Unesco Committee spiked both candidacies, advising the groups to come back united next year.

Mr. Niola called the bid from Treviso “an act of war by the north against the south.” The anthropologist, who has worked on Naples’s bid, said the clash is the latest example of latent tensions between north and south that date back to the country’s 19th-century unification, that are fed by diverging economic fortunes and that periodically flare up.

The Treviso-based Consortium for the Safeguard of Traditional Italian Espresso Coffee sought to celebrate the ritual around Italian coffee-drinking and the Italian way of making espresso, rather than regional peculiarities, said founder Giorgio Caballini.

In the south, he said, “They want to say that coffee comes from Naples, but such prevarication is unacceptable. “It means appropriating something which isn’t only theirs. It is also theirs.”

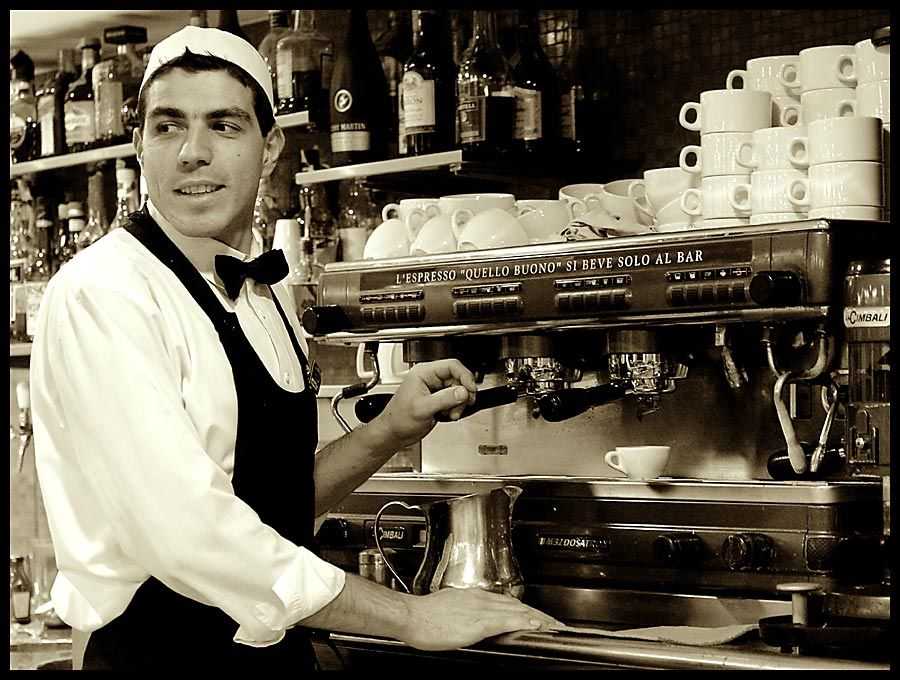

It should be noted that the espresso machine was invented in Turin (northern Italy) patented by Angelo Moriondo in 1884, which revolutionized the way of serving the beverage, giving baristas the opportunity to produce many cups in series. Luigi Bezzera, Desiderio Pavoni, Pier Teresio Arduino and Achille Gaggia contributed to the spreading of espresso: innovators who made significant changes, thus electing Italian-style coffee famous throughout the world.

In Naples, what was at play with the Unesco candidacy touched on some deeply rooted identity issues.

“Espresso is like pizza: It has become an Italian symbol, but its unique culture and roots are Neapolitan,” said Nando Cirella, president of the Neapolitan Espresso Association.

The city’s bid centered on rituals surrounding espresso in Naples and celebrated in movies, plays and books. Best known is the “suspended coffee” tradition, in which customers pay for their coffee while leaving enough extra to pay for a cup for those in need.

A possible common Unesco bid must recognize this unique Neapolitan coffee culture by enshrining it in the title, said Michele Sergio of Gran Caffè Gambrinus, who transformed the cafe into a war room for the bid, gathering more than 40,000 signatures.

Not exactly, said Mr. Caballini, from the Treviso-based consortium. “I am not going to give away a part of the name in favor of a small part of Italy,” he said. Some on both sides say everybody loses in this situation.

Hence, a peace proposal from Daniele Pugliese, a comedian and a founder of Casa Surace, which makes funny videos playing on north vs. south stereotypes. “Food should be like nonnas,” or grandmothers, “who unite the country,” Mr. Pugliese said.

“Let’s leave it to the nonnas,” he said. “They’ll be able to find an agreement.”