Climate change is threatening Europe’s coffee supplies, but the impacts could be diluted by planting the crops amongst trees – a technique known as agroforestry, which is also being revived in European farming.

The distinctive waft of freshly brewed coffee is a familiar wake-up smell but, next time the aroma tickles your senses, take a moment to think about where your morning cup originates.

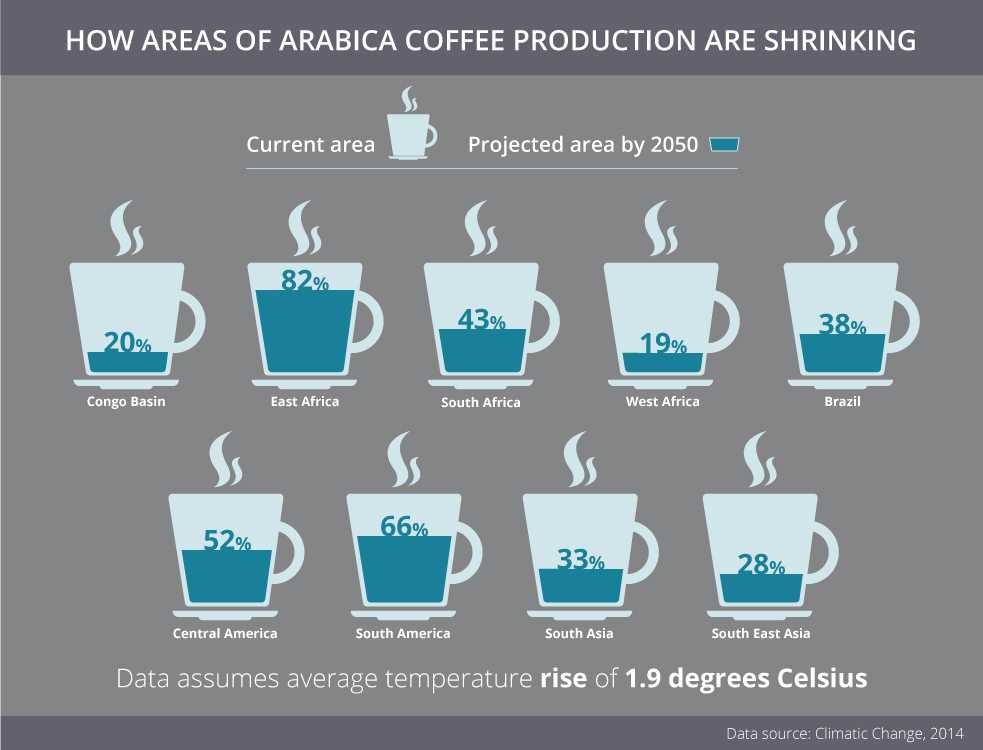

The top producers of arabica coffee beans today are in Brazil, Vietnam, Colombia and Indonesia, and half of all coffee is grown under full sun. These exposed coffee trees are increasingly vulnerable to the effects of climate change.

‘With global warming, coffee producing in Brazil will be dramatically reduced, by perhaps 70 percent if it continues to be grown in full sun,’ said Dr Benoit Bertrand, coffee expert at CIRAD, the French agricultural agency.

However there is an alternative way to grow coffee, one which harks back to its origins in the forested highlands of Ethiopia where wild coffee grew in shady forests. The idea is to grow the crop in the shade of taller timber or fruit trees, in so-called agroforestry systems. It is also the only way to grow coffee and preserve mountain soils.

‘This system is really good for preserving biodiversity, but the profitability of the system is lower,’ Dr Bertrand said. This is why many large plantations continue to plant coffee in full sun, even though it requires expensive pesticides and sometimes irrigation.

In fact, up until now, new coffee varieties were developed in Brazil and Colombia and were bred to thrive in full-sun plantations. Meanwhile, agroforestry coffee growers have had to plant less productive coffee varieties.

Dr Bertrand leads the EU-funded BREEDCAFS project which has begun working with industry, plant scientists and the World Coffee Research organisation to assist these growers by creating new arabica coffee that will generate better yields under forest canopies.

‘Productivity is around 30 percent lower (in agroforestry), but they are using varieties not adapted to agroforestry,’ explained Dr Bertrand. ‘We believe that we can increase it considerably by selecting trees that are more vigorous and adapted to shade.’

Hybrids

The strategy is to cross wild Ethiopian coffee trees with American plantation coffee to produce hybrids that coffee growers in Central America, Africa and Southeast Asia can choose from.

Dr Ronan Sulpice, a plant biologist at NUI Galway in Ireland working on the BREEDCAFS project, is investigating the genetics of coffee so that the breeding of improved shade-grown arabica can be speeded up.

‘We want to understand which parts of the genome are important, so we can orientate breeding efforts and save time and effort,’ he explained. ‘(We) will then help with new varieties but also help these small farmers work together with roasters to get better income for their coffee.’

The project will partner with growers in countries such as Nicaragua, Cameroon and Vietnam and will seek to set up new networks of coffee growers and roasters. As the new varieties should also be less demanding in terms of fertilisers, the partners may consider some sort of certification for this agroforestry coffee, so that consumers can learn about its environmental and social benefits.

Ultimately, this is a win-win for coffee growers, the roasting companies and consumers. ‘The quality of the coffee from agroforestry is better than the coffee you get in full sun,’ said Dr Bertrand. ‘It is also better for biodiversity and uses far less pesticide.’

Farming

It is not just tropical countries that benefit from agroforestry. Mixing trees with farming in Europe can deliver environmental upsides. Planting or maintaining trees can reduce water run-off, stop soil erosion, store additional carbon and encourage biodiversity. These benefits can be especially impressive on arable farms where trees traditionally were lost as farming intensified.

However, the value of trees has often been underestimated in the past.

‘There was a tendency to remove individual trees from the landscape in the 1970s and 80s, but there has since been growing appreciation of the environmental and production benefits trees bring,’ said Dr Paul Burgess at Cranfield University, UK, coordinator of the research project AGFORWARD, which is promoting agroforestry in Europe.

There is more agroforestry than people realise. Data from AGFORWARD revealed that agriforestry comprises almost 4 % of Europe’s land area, or almost 9 % of its agricultural area.

Trees can also offer shelter and food for farm animals. Examples include wood pastures in Germany where pigs forage beneath apple trees, the Dehesa oak pastures of Spain where sheep graze beneath trees grown for cork and poultry breeding under olive trees in Italy.

‘Agroforestry should be considered in any meaningful land use policy,’ said Dr Burgess. The project has worked with over 40 farmer and landowner groups to determine how trees and farming can be integrated into orchards and olive groves, on arable farms and in livestock production including free-range poultry.

The project has also recommended changes to current EU agricultural policies to promote agroforestry. While tree-planting is supported in some policies, Burgess says the measures are currently too scattered.

‘We need to show how trees can be integrated into farming landscapes without making it an administrative burden (in terms of policy),’ Dr Burgess explained. ‘It would be clearer for farmers and administrators if the varied measures that can support tree planting, maintenance and use on farms are highlighted and brought together in one place.’