When Jennifer Poni Joel Donga introduced the stories of fellow coffee farmers in South Sudan to an audience in Paris last year, she was glowing with pride.

In the French capital for the sales launch of Africa’s newest country’s first batch of coffee, she said “the farmers are very excited and they are happy” about the prospect of cups of coffee being the first non-oil export from the war-ravaged country.

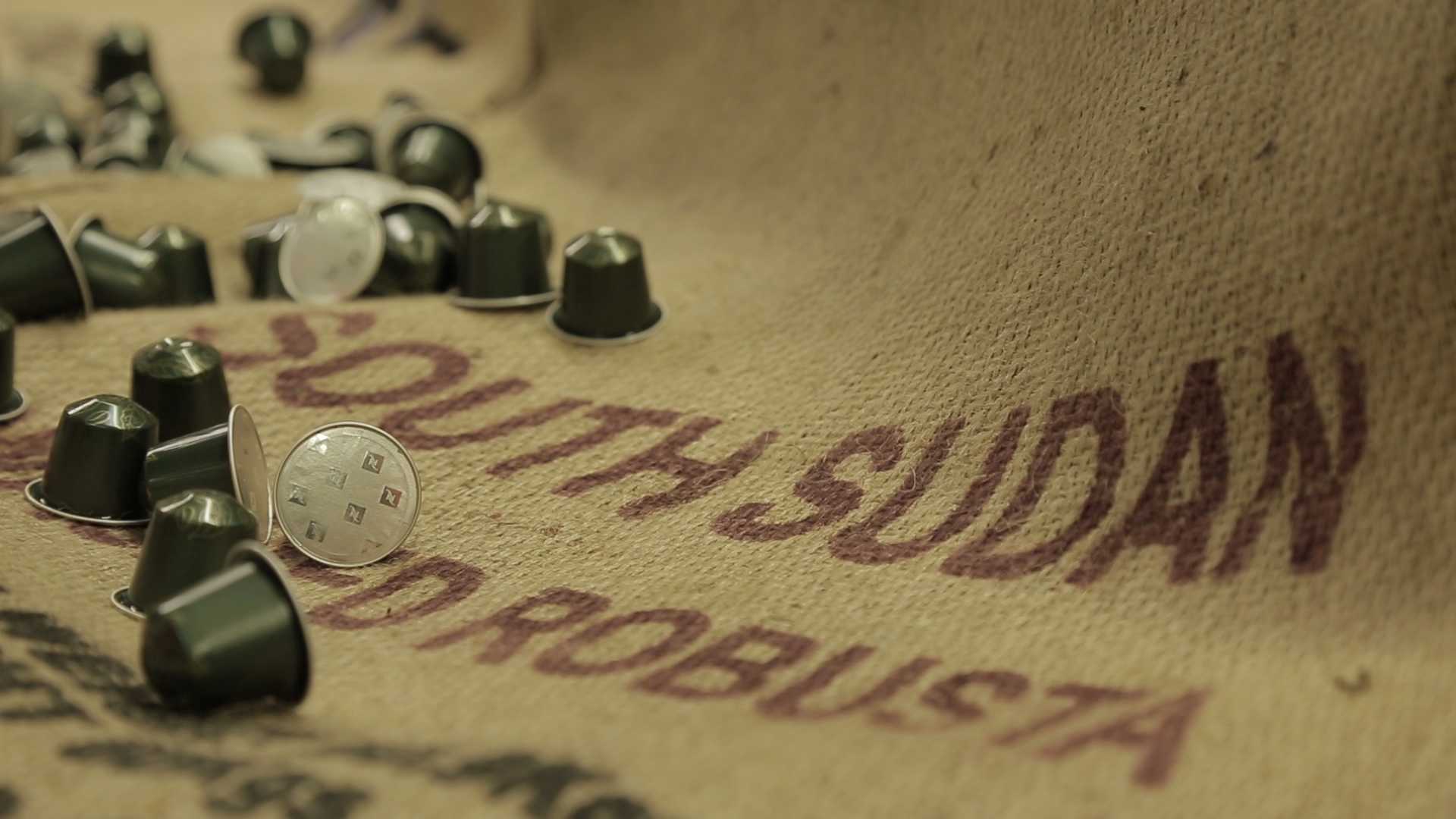

Following last year’s limited edition sale in France, her coffee community in South Sudan’s southwestern city of Yei has in 2016 produced enough beans for Swiss capsule maker Nespresso, which has been working alongside the development non-government organisation TechnoServe, to offer capsules in five more countries.

This year’s launch, however, has been overshadowed by further violence in South Sudan, this time involving Yei, which had hitherto been relatively peaceful.

TechnoServe has been temporarily forced to withdraw its staff and suspend farmer training, while Ms Poni, who is also an agronomist helping other farmers, has left her farm in Yei for a safer part of the country.

The coffee bean and conflict have historically gone hand in hand, but the surge in popularity of specialty, or premium coffee over the past few years has spurred the search for different tastes.

This has taken coffee merchants and roasters to new frontiers, including former conflict areas where tensions still simmer as well as active war zones.

With an increasing number of roasters catering to the “hipster” market, buying their beans directly from the grower as well as large coffee traders such as Neumann, Ecom and Olam offering gourmet beans, the specialty market is an increasingly crowded place with new flavours and growers’ unique stories giving the coffee a competitive edge.

Provenance

“People like to know where their coffee comes from to be inspired,” says Richard Hide, head of trading and marketing at Twin, a UK development NGO, with projects in Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), although he adds that “it wouldn’t work without the quality” of the beans.

From the single-serve capsule in a home machine to the artisanal drip brew, more than half the coffee consumed in the US is specialty, or gourmet, up from 40 per cent six years ago.

Compared with a US national retail average of about $4.40 a pound, specialty beans are retailing at just under $28, up 15 per cent over the past two years, according to transparenttradecoffee.org, a website promoting transparency in the gourmet coffee market.

The higher prices that consumers in developed markets are willing to pay have allowed roasters to search for beans in ever more exotic destinations. The higher the risk, the greater the cost, including development investment and logistics.

This year, a limited amount of coffee from Yemen, which is in the throes of civil war, was priced at $173 a pound through Blue Bottle, a leading US west coast roaster, revealing the extent that the coffee cognoscenti were willing to pay for high-quality beans with the scarcity value.

Although the move towards premium products has driven the search for new coffees, the economic viability of growing the crop has been thrown into question for a wide group of farmers as many struggle to make a living. A volatile futures benchmark contract and rising costs are driving growers away from coffee to more profitable crops or to abandon coffee production.

“Farmers who can produce differentiated good coffee can get a premium for that. Other farmers who are highly productive and in a country with a low currency will also do well,” says Carlos Mera, a coffee analyst at Rabobank. However, smallholder coffee growers with low productivity and high costs, producing beans that lack the premium quality, are struggling to survive.

Growers’ struggle

The International Coffee Organisation recently warned that although coffee was one of the leading performers on commodity markets this year, rallying by almost a quarter since the start of the year to above $1.60 a pound , many growers in many parts of the world still failed to receive enough money to cover their cost of production.

On the other hand, Nespresso, for example, offers growers in its “AAA” sustainability programme 30-40 per cent more for their beans compared with the benchmark price, and 10-15 per cent above beans of similar quality.

At current market prices, farmers in Yei would receive at least $2.10 a pound. Twin says it pays its growers in the DRC about $1 over market prices, amounting to $2.60 a pound.

The growing divergence in what the coffee grower receives is highlighted in the difference in the bean prices for the winners of the Cup of Excellence awards, which are tasting competitions held around the globe for gourmet coffees.

Winning beans are sold in wholesale online auctions, with most of the proceeds going to the grower. In 2015, the average price for the winners’ beans was $7.72 a pound, according to transparenttradecoffee.org, six times that of the arabica benchmark.

The frontier coffee regions also offer roasters exciting “narratives” through which they can appeal to coffee drinkers. The stories of how the coffee came to be grown and the benefits it offers the communities can often intrigue and create a special connection with consumers, say coffee executives.

The enthusiasm over gourmet coffees, and the potential returns from coffee production, have attracted aid organisations, philanthropic foundations and corporations to try lift the livelihoods of war-torn areas through coffee growing.

Twin’s Mr Hide says: “You have high-quality coffee which is valued and appreciated and you have the social impact to being able to engage in that market. The result of that presents a catalyst to change.”

Volatile market

Conflict can be a “double-edge sword for roasters and retailers”, according to Ewan Reid, technical director at Matthew Algie, a Scottish coffee roaster who has been buying beans from the DRC through Twin. “Some consumers will wonder ‘how on earth can it be good’ while others might say ‘it’s good to be supporting coffee from that region’,” adds Mr Reid.

The volatile market environment means it is also difficult for development projects to be viable, and the potential conflict adds another complexity, even if a community can deliver specialty quality coffee, say experts.

“In the last decade, dozens of projects have come across my table. Four out of five are completely unworkable,” says David Barry, a coffee consultant working in Africa.

Of the handful of proposals given approval, many remain aid projects that may or may not be able to continue once the development funding ends.

“It really doesn’t do us any good if a small group benefits because its coffee is subsidised by charities or the price is supported by consumers’ good will,” says Mr Barry.

Nespresso, which has invested SFr2.5m in South Sudan since 2011, says its projects need to make business sense. But they are also aware that they have to take a long-term view.

On the ground in South Sudan, many of the farmers have been forced to leave their farms. According to TechnoServe, which is hoping to resume training through radio, some are hiding in the bush. While some have been able to occasionally return to tend to their coffee farms, others worry about their future if and when peace arrives.

Ms Poni firmly believes she and her community of coffee farmers are building a legacy for South Sudan. She says in an email via TechnoServe: “That the coffee is now sold in more countries I feel very proud of indeed. Even though South Sudan is in conflict, our coffee is sold outside. Let the world not feel that though we are in conflict, we will not send them our coffee.”