In April 1865, at the bloody, bitter end of the Civil War, Ebenezer Nelson Gilpin, a Union cavalryman, wrote in his diary, “Everything is chaos here. The suspense is almost unbearable.”

“We are reduced to quarter rations and no coffee,” he continued. “And nobody can soldier without coffee.”

If war is hell, then for many soldiers throughout American history, it is coffee that has offered some small salvation. Hidden Kitchens looks at three American wars through the lens of coffee: the Civil War, Vietnam and Afghanistan.

The Civil War

War, freedom, slavery, secession, union — these are some of the big themes you might expect to find in the diaries of Civil War soldiers. At least, that’s what Jon Grinspan, a curator at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, assumed when he began digging through war journals in the nation’s Civil War archives.

“I went looking for the big stories,” Grinspan says. “And all they kept talking about was the coffee they had for breakfast, or the coffee they wanted to have for breakfast.”

The word coffee was more present in these diaries than the words “war,” “bullet,” “cannon,” “slavery,” “mother” or even “Lincoln.” “You can only ignore what they’re talking about for so long before you realize that’s the story,” Grinspan says.

Union soldiers were given 36 pounds of coffee a year by the government, and they made their daily brew everywhere and with everything: with water from canteens and puddles, brackish bays and Mississippi mud — liquid their horses would not drink. “Soldiers would drink it before marches, after marches, on patrol, during combat,” Grinspan tells us.

The Confederacy, on the other hand, was decidedly less caffeinated. As soon as the war began, the Union blockaded Southern ports and cut off the South’s access to coffee.

“The Confederates had access to tobacco and Southern foods; Northern soldiers had access to coffee,” explains Andrew F. Smith, a professor of food studies at the New School in New York, and author of Starving the South: How the North Won the Civil War. “When there was not a battle going on, Confederate soldiers and Union soldiers met in the middle of fields and exchanged goods,” Smith says.

Desperate Confederate soldiers would invent makeshift coffees, Grinspan tells us, roasting rye, rice, sweet potatoes or beets until they were dark, chocolaty and caramelized.The resulting brew contained no caffeine, but at least it was something warm and brown and consoling.

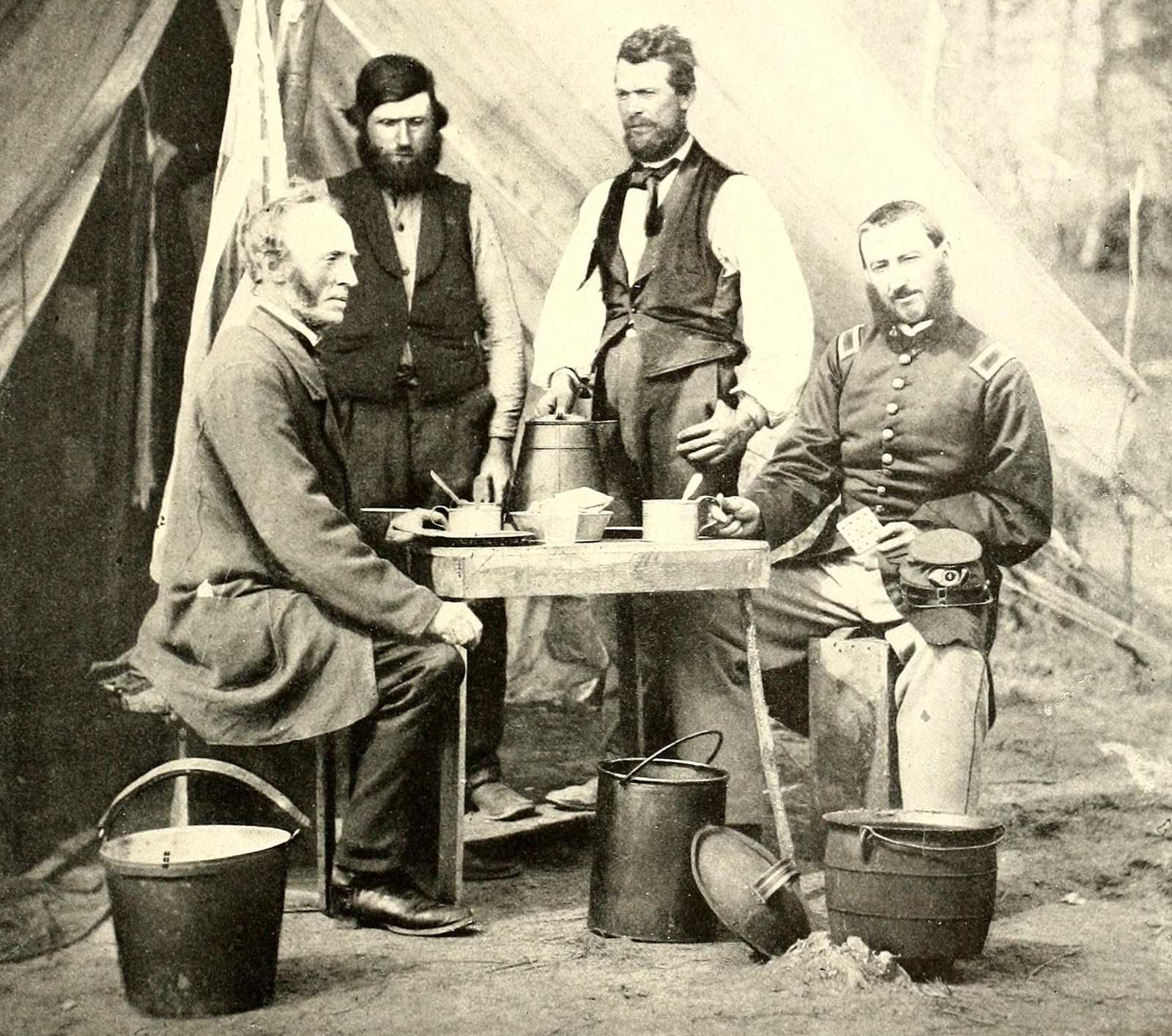

How did the food taste? These faces say it all. Photograph from the main eastern theater of war, Meade in Virginia, August-November 1863.

Perhaps the North’s access to caffeine gave its soldiers a strategic advantage. At least that’s what one Union officer, Gen. Benjamin Butler, thought. He ordered his men to carry coffee in their canteens and planned attacks based on when his men would be most wired. His advice to other generals was: “If your men get their coffee early in the morning, you can hold.”

Over the course of the war, as the Union army grew, its camps became makeshift cities, housing hundreds of thousands of men. “They were in battle maybe one or two weeks of the whole year,” Grinspan says. Most of the time, he adds, “they weren’t shooting their rifles at enemies, being chased or fired upon, but every day they made coffee.”

In 1859 Sharps Rifle Co. began to manufacture a carbine with a hand-cranked grinder built into the butt stock — or handle — of the rifle. Union soldiers would fill the stock with beans, grind them up, dump them out and use the grounds to cook the coffee. As the morning began, one Civil War diarist described a scene of “little campfires rapidly increasing to hundreds in numbers that would shoot up along the hills and plains.” The encampment would buzz with the sound of thousands of grinders simultaneously crushing beans. Soon, tens of thousands of muckets (coffee pots) gurgled with fresh brew.

“Here’s an irony,” says Grinspan. “These soldiers who were fighting ostensibly to end slavery are fueled by this coffee from slave fields in Brazil.”

The Vietnam War

Coffee may have powered the Union army during the Civil War, but during the Vietnam War, it fueled the GI anti-war movement.

In the late 1960s and early ’70s, as soldiers returning from Vietnam began to question the U.S. role in the war, GI coffeehouses sprung up in military towns outside bases across the country. They became a vital gathering place.

David Zeiger helped run the Oleo Strut, a GI coffeehouse outside Fort Hood in Killeen, Texas, for three years in the early 1970s. “An oleo strut,” he explains, “is the vertical shock absorber on a helicopter. The concept of the GI coffeehouse was as a shock absorber, a place where GIs could get away from the military and say what they really felt,” Zeiger says. In 2005, Zeiger, now a filmmaker, made Sir, No Sir, a documentary about the GI anti-war movement and the story of the Oleo Strut.

The first GI coffeehouse — called UFO (a play on USO) — opened in 1967, near Fort Jackson in Columbia, S.C. It was founded as a “hangout for GIs” by Fred Gardner, a Harvard grad who joined the Army reserves in 1963.

“The UFO became a place where soldiers could gather and talk openly about their worries and frustrations, without the military brass around,” Gardner recalls. And in Columbia, says Gardner, UFO was a rarity — a place that “not just black and white but students and soldiers” could share.

Other GI coffeehouses followed — around two-dozen by 1971, by some accounts. They included the Shelter Half in Tacoma, Wash., near Fort Lewis; the Green Machine outside Camp Pendleton in San Diego; and Mad Anthony Wayne’s in Waynesville, Mo., outside Fort Leonard, to name a few. As the anti-war movement heated up, these coffeehouses became places where GIs could get legal counseling on issues like going AWOL and obtaining conscientious objector status, and learn about ways to protest the war.

Many coffeehouses also began publishing newspapers, with exposés on poor conditions within military prisons, op-eds from disillusioned soldiers and information about rallies and demonstrations.

GI coffeehouses caught the eye of those leading the anti-war movement in Hollywood. Actress Jane Fonda’s anti-war road show, the FTA — an alternative to the USO shows that she created with Donald Sutherland — frequented the GI coffeehouses. The first time Fonda visited the Oleo Strut, the local newspaper had a big headline: “Barbarella comes to Killeen, Texas” (a reference to Fonda’s role in a 1960s sci-fi cult film).

The coffeehouses also drew the attention of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s administration, which monitored their “subversive activities.” In August 1968, Army Chief of Staff Gen. William Westmoreland sent LBJ a secret memo noting, “consensus is that coffeehouses are not yet effectively interfering with significant military interests, and, consequently, suppressive action may be counter-productive,” as sociologist Tom Wells details in his book The War Within. The next month, however, Westmoreland reported to Johnson that several Oleo Strut frequenters had been arrested.

Afghanistan

“The military runs on coffee,” says Harrison Suarez, co-founder of Compass Coffee in Washington, D.C. “The Marines especially. It’s this ritual.”

Suarez and Michael Haft, who started Compass together, “first became friends in the Marines over coffee,” Suarez says, “learning how to navigate with a map and compass.” On their first day of training in North Carolina, it was, “Hey, Gunny, want to get together for a cup of coffee?” recalls Suarez. “That’s how pretty much every new relationship in the Marines is formed.”

As the war in Afghanistan intensified, both Suarez and Haft deployed there with the 1st Battalion, 9th Marines. One of their missions was to help develop the local police force and army. The two men tried to bond with their new Afghan partners over coffee, Suarez recalls, but the Afghans weren’t having it.

“Any time we shared coffee with our Afghan partners, it was just a train wreck,” Haft says. The Afghan culture is much more about tea. It was important to the friends to embrace local culture, so they quickly learned to stop pushing the java. Regardless of what was in the cups, the experience of gathering together over a hot drink and “taking time to develop a rapport with your partners that you are fighting alongside holds the same,” says Suarez.

But it was coffee that fueled the American troops stationed there, with Marines sharing morning brew with their platoon commanders as they all gathered to discuss the day’s plans. As it was a century earlier, coffee became a ritual of war.

When Haft and Suarez returned home after their deployment, their coffee obsession deepened. “Everybody gets into something when they return home from the war. For us, it was coffee,” says Haft. A quest to learn how to brew the perfect cup first led them to write a book, and eventually to open Compass Coffee, a roastery and community gathering place in northwest Washington, D.C.

And they haven’t forgotten their time with the Marines, where their passion for coffee first took root. “We’ve sent coffee to Marines on aircraft carriers, to Afghanistan,” Haft says. “Basically any time any soldier requested some crazy coffee delivery, we’ve done our best to accommodate getting it out to them.”

The business has started to expand quickly — there are now several branches of Compass throughout the city, and tins of Compass’ signature roasts are available at several local grocery stores.

Marines

When we visited them at their flagship coffee shop in northwest D.C., the roaster was going strong and new equipment was being installed in the cupping room. The weekly schedule was posted in the staff room, designed using organizing strategies the two friends learned in the Marines.

Over a cup of Compass brew, Suarez summed things up. “Going back all the way to the Civil War and up to our experience in Afghanistan, you’ve got this common thread of people coming together, sharing their experience, their stories over coffee.”